I am stuck with this sense that my life split in half as soon as I was sent to boarding school a month before my eighth birthday. From that moment, the two opposing realities of School and Home have had the same weighting. School wasn’t just part of a continuous life. It was its own life. And Home was another life. A life called Holidays. But what was home before these two lives?

Turkey

This is how the story goes. On October 8 1955, my mother clambered on to the ping-pong table in our British Embassy flat in Ankara and, with the help of my father, gave birth to me and fainted. The doctor had been called but he hadn’t arrived in time. The umbilical cord, still attached to the placenta, was wound tight round my neck and I was turning blue. My father hadn’t got a clue what to do. Just as he was trying to unwind the cord and free me from being strangled to death, the doctor arrived with a pair of scissors. My father (to my delight) told this story many times over the years, with cliff-hanging comedic timing. But he didn’t tell it as Super Dad to the rescue; mum was always the superhero for facing the agony of giving birth in the first place (and not demanding that she be flown home to have me in an English hospital, like the other diplomatic wives whom she always described as being ‘wet’ for doing so). No. Dad told it with him playing the part of bungling fool who just happened to save my life.

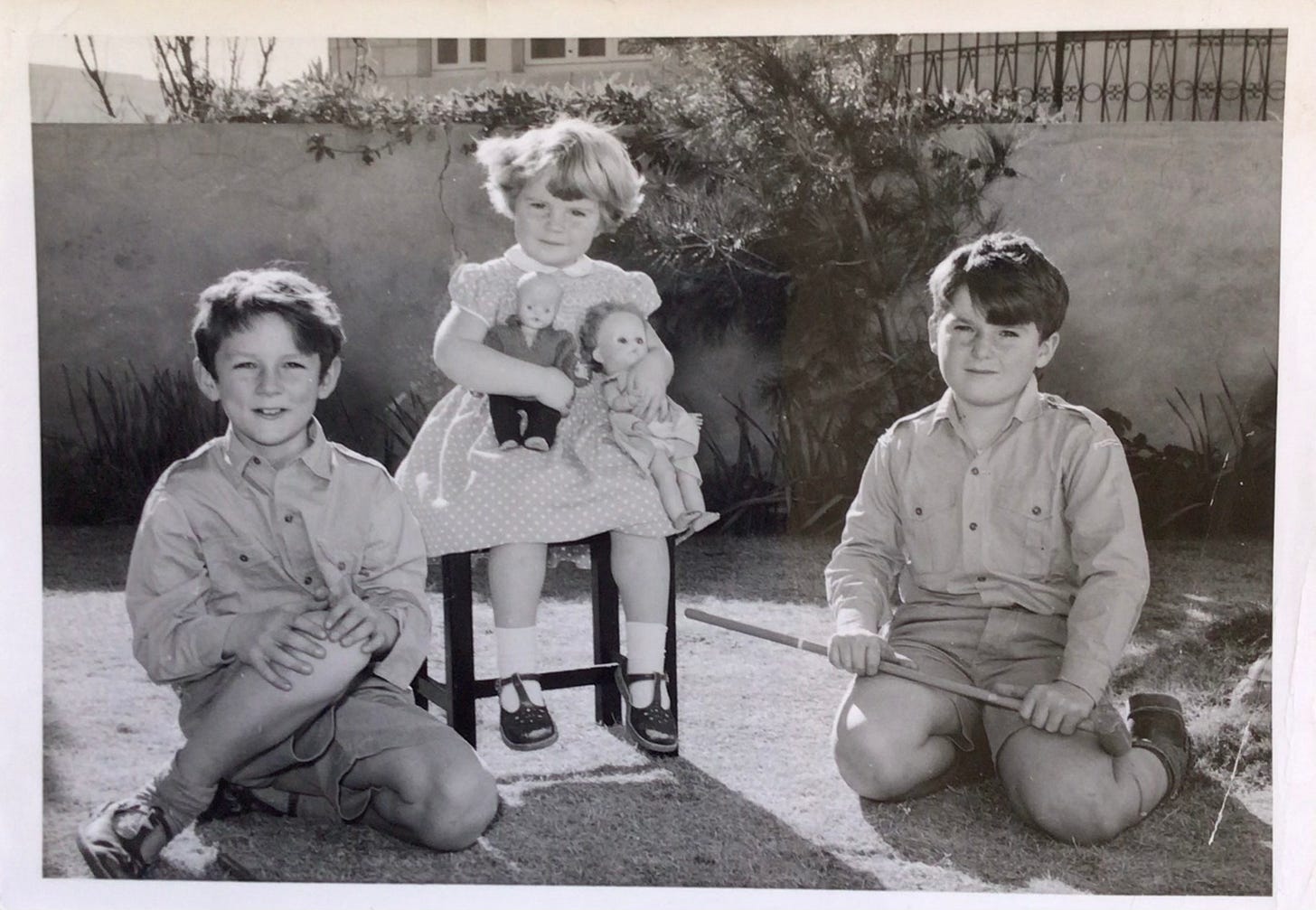

My memories of the first three years of my life in Turkey are entirely born of family anecdote and the odd photograph. My brothers were five and six when I was born. I had a nanny from birth. Her name was Lisa. She was Austrian and, much to my parents’ amusement, my first words were in German.

I have always lived with the knowledge that Lisa was solely my nanny (not my brothers’) and that she was devoted to me and I adored her. But at the start of my life, the anecdotes testify to my parents having some involvement in feeding me. There was, apparently, some attempt to attach me to my mother’s breast but this was soon ditched in favour of bottles; my mother said she couldn’t feed me because she had inverted nipples - whatever that meant - and anyway breast feeding was basically a load of nonsense. My father was certainly involved in my early feeding because he was always proud of getting rid of what my parents called ‘The 2 a.m Feed’ by giving me a bottle of water instead of milk when I was about 4 weeks old.

In the boiling hot summers, the British Embassy in Ankara moved to a yalı (mansion) on the shores of the Bosporus in Istanbul. I know from family stories and a handful of photographs that this involved long drives (days?), often on unpaved roads in the heat, with my brothers and me (presumably sitting on Lisa’s knee) squashed into the back and my mother in the front, smoking, next to my father (also smoking) at the wheel. The car was a Morris Traveller, I think - evidence being one photograph of my brother taken by the roadside captioned ‘on the road to Istanbul’. This was years before we graduated to chauffeur-driven cars flying the Union Jack.

We left Turkey when I was three. I have been back several times. The first time was on an overland trip from Iran (where I was living at the time). But it took until I was forty to do something about learning the language. I decided to go to university for the first time and chose Turkish as my subject. I have been learning and loving Turkish ever since. Istanbul is one of my favorite cities - probably because I’m back to that holiday-is-home feeling.

But that feeling isn’t triggered by Turkey alone. It happens anywhere there is blazing sun and dust, sharp shadows and watermelon, mosques and horn-honking streets, and cool, plush rooms in compounds. And there’s a whole load more shameful jewel-in-the-crown sensory tropes that conjure up a vaguely colonial collage of a privileged life in embassies. I’m not proud of this. It is at odds with what - I think - I have become. But it’s there. Ready to be instantly awakened by a smell, a sound, a taste or a touch of my childhood.

Turkey at least has mostly uncoupled itself from the influences of my childhood and my class background.

Jordan

I have actual memories of Jordan.

I remember our big white house in Amman. I see a glaringly white, pristine path leading up to the front door. I am looking down at it. Staring at something dark brown on the path. It is a large, neat, sausage-shaped turd, just laid by me. I can’t remember the consequences.

I remember a palace with big gates. I used to go there in a big black car. Inside the palace was a princess. She was my friend. I remember liking her. We played with dolls sitting on the floor of a massive bedroom. The princess was King Hussein’s daughter. She was exactly the same age as me. The story was that my mother, unlike the other British mothers of four year olds, was quite happy for me to be dropped off at the palace alone - without her or a nanny - to play with the princess. She was the king’s first born and had no siblings. Maybe the plan was for her to learn English from me as well.

Egypt

I had my fifth birthday in Cairo. The store of memories is increasing.

I can remember …

Our car jammed between honking cars on the street. The sweet smell of garlands made from jasmine buds hanging on the arms of the boys who were selling them, as t

hey ran between the cars.

The safe soapy smell of my father’s clean shaven face as he held me in his arms on a balcony at night to watch the sky explode with fireworks.

The endless joy of swimming for hours and hours in the big pool at The Gezira Club. I have always remembered it was called The Gezira Club. A much told anecdote is how I was on my own in the street one day and hailed a taxi. I asked the driver to take me to The Gezira Club. And he did.

The interminable thwack, thwack, thwack of a tennis ball hitting gut-stringed racquets as I sat bored on the grass beside the court while my parents and their friends played tennis. I remember the sting of ants biting my thighs.

Carefully forming loopy letters on a tiny blackboard. The loopy letters were the start of reading and writing in French. It was a French school run by nuns. I remember their nun outfits.

In the desert, sitting on the back of a horse, clinging on to the rider, a man called Sayid. My brothers and my mother, each on their own horse, behind us. Galloping past the pyramids, stopping in front of the Sphinx to check if the Sphinx was smiling at me. Sayid said that if the Sphinx was smiling at me, he’d pluck me a tangerine from the next tangerine grove. The Sphinx always smiled at me. I always got a tangerine.

England

From the age of six until I went to boarding school, we lived in a semi-detached Victorian house in Dulwich, London. This sits apart from all my other childhood memories. An island on its own. Not home-is-holiday, not School. I did go to school, of course. I went to a day school and was picked up by my mother in the afternoons. I remember rushing out to her in the playground with ink stains on my fingers and my uniform. She never fussed about that kind of thing. Apart from that, I remember very little about the school except that I enjoyed it and I had friends. I can see myself playing often at a particular friend’s house, but I can’t remember her name. My father went to work in the morning and came back in the evening, like a normal father. We had a rabbit called Hoggs and a Siamese cat who didn’t have a name but was referred to as Dog or Catting-Ass.

The only bad memories I have are my mother telling me to stop fidgeting when I climbed into bed with them (not a usual event; I can only assume I had wet the bed) and my cruelty to the cat in my bedroom. I loved the cat, so I don’t know why I did what I did. I shut the cat in one of my drawers and I pulled its tail. I still feel haunted by the guilt and remorse.

My other key memories are …

Dad reading to me in bed at night, doing silly voices for the characters in Milly Molly Mandy.

Ice skating with mum in Streatham ice rink.

Making myself marmalade sandwiches for breakfast and cycling to Dulwich Park on my own one early sunny morning.

Being allowed to watch Dixon of Dock Green with my parents.

Tobogganing down a big hill with my father.

Worrying about a Third World War — I remember my father coming home from the Foreign Office much later than usual in a very agitated state. I remember him answering my questions about Cuba and missiles and a man called Krushchev.

There were no nannies or cooks or servants in that house. My parents’ diplomatic social life carried on in London, but I have no memory of baby sitters. My only memory of them being out at night is the night they went out and paid me to babysit myself.

I have very few memories of my brothers during that time (they were already at boarding school). I can see them playing darts in the dining room and I can see them acting in a play version of Steptoe and Son directed by me. We performed it in the garden to an audience of my parents. I also had the star part. I was Old Steptoe, the 12 year old brother was Young Steptoe and the 11 year old brother was The Girl, or ‘the bird’ as we referred to him in the play. How on earth did this happen? I can only imagine my parents must have bribed them to do my bidding.

Reading through these memories, I am struck by how happy they are, how romantic. All I can say is they are the stock memories of the first seven years and eleven months of my life that I have always carried with me.

And then I was sent to boarding school.

So good to have these scenes alongside the Drying Rooms chapters. As you say Emma - dark and light.

Oh, Emma, what a childhood you had, one that is so interesting to read at the same time as reading The Drying Rooms. That you have been able to write your life, as I think of it, is remarkable. What myriad experiences, places and people. I also enjoy the little "portraits" of your mom and dad.