Audio version of Chapter Twenty Seven

The first part of this letter is contained in the previous chapter

Dear Mum and Dad [continued],

Mum, I think it would move you to know that I am writing this at the long, narrow oak table that used to be in the telly room in Devon. On the right-hand side of my lap top there is a dark mark on the wood. I’ve just rested my index finger on it. It’s one of the cigarette burns left by you on various bits of furniture. They are hard to discern on the oak table, because they merge with the wood’s variegated grain, it’s natural whorls and knots, as well as generations of faint rings left by wine glasses and coffee mugs. But I can spot all your burn marks.

It used to drive me nuts the way you left lit cigarettes on the edges of things. It was so slapdash and dangerous. But now each of these ghost marks triggers love — and guilt.

Several years after Dad died, your carelessness nearly killed you (but by then dementia was creeping into the mix). I remember being woken by the call from Derriford Hospital. A screaming ambulance had rushed you there at two in the morning. You had fallen asleep with a lit cigarette. I asked if I could speak to you and I remember the surge of relief when I heard your undaunted familiar voice on the phone. You were bewildered but you were also cross. You already had it in for the doctors and nurses. They keep telling me I’m suffering from smoke inhalation! I’ve never heard such rubbish!’

I’m telling you this story Mum because it’s made many people laugh. And I think it would make you laugh too. There are so many black-comedy stories about you that have now been passed down and mythologised in the telling.

I remember the deliciousness of laughing with you, but also the agony of it when it was inappropriate. The worst was at granny’s funeral. Your mother, Dad. But you weren’t there. From my memory, you were locked in a Falklands War debate at the security council in New York. It was Rupert, Mum and me who went and I’m still appalled that the three of us made the front pew shake with an infectious bout of helpless giggling. What caused that shameful torture? Who started it? Rupert? Very likely. Me? Unlikely. Or was it you, Mum, with your visceral loathing of anything that smacked of pomp, ceremony and ritualistic expectations?

You hated funerals. We didn’t give you a funeral. Nothing. No one attended. I had to be very firm with the undertaker over the phone. ‘No. Nothing. No one … no, not even me … No, please don’t lay flowers on her coffin. She would have hated that.’ And you would have. You hated flowers stifled in plastic wrapping. You hated coffins. You always said they made you feel claustrophobic. And judging by your – our — appalling conduct at granny’s funeral, you couldn’t trust your own behaviour.

But years after granny’s funeral, there was another you went to. Simon’s. In West Norwood cemetery. I think going to the funeral of your son, the first son to die, probably finished you off when it came to funerals. You didn’t go to Rupert’s five years later and you didn’t go to dad’s. You refused to have anything to do with it. We couldn’t even discuss it with you.

Oh Mum. There is a guilt in me about that period after Dad died that I can’t get to the heart of. Your grief manifested itself in such difficult, alienating behaviour that … that what? It was hard to comfort your broken heart, Mum. The only person who could have done that was Dad.

Dad, you sometimes said to us, ‘don’t take Mum so seriously’. You said it with a slightly quizzical smile, not towards you Mum, but towards our fervent over-caring about your moods, your sharp tongue, your propensity for taking a wrecking ball to the simplest of moments, like preparing for a family walk. But sometimes being with you was delicious — or just right.

Mum, I had a whopper of a dream about you recently. The dream contained me losing my temper with you. A rare thing. Really shouting at you. On waking into the few seconds of liminal space before remembering that you are dead, my arrhythmic heart was going berserk with the shock of it … I can’t catch the dream … except for the word scathing … you were scathing about something crucial about to happen … you wrecked it … no … I wrecked it … I lost my temper.

What I’m trying to say, Mum, is that I woke up full of the feeling of you and was totally shocked by this dream because I wish it had been a gentle dream permeated with love and understanding, acceptance and redemption —all of this is the way I have moved towards feeling about you. And I think my Aslanisation of dad must have — might have? — been painful for you.

Did you really think I loved Dad more than you? You said so. ‘Of course, you love Dad more than you love me.’ More than, less than, the same as … I can’t measure love in this way. You were difficult, Mum. Mercurial. Moody. Difficult to be around. Maybe you didn’t feel as loved as Dad because you sensed the kid gloves, the eggshells, the faux authenticity, the embarrassed recoiling. Even in the final, grim care home, your characteristic, misplaced, outspokenness was still alive and well. ‘Oh, here comes fatso,’ you always said loudly when the only carer you actually liked approached you with a little plastic beaker full of pills (which you used to spit out). How you raged against their sing-song voices and competent hands!

Of course, I will never forget that sudden, lucid moment with me when you broke the long care-home silence and said, ‘I wasn’t a very good mother to you, was I?’ which I refuted of course. I couldn’t bear this reductive thought being one of the last to buzz in the broken hive of your mind. Usually when I said, ‘I love you, Mum’ (which I said a lot because it was true and there was little else to say) you responded, ‘I love you too, darling.’ It was a peaceful refrain between us. But one time you broke it with a different tone, ‘You say that. But I wonder … You’re a good girl, darling. You do your duty.’ And it was painful because there was truth in it. And not truth in it.

There is a terrible irony about your time at that care home, mum. You loved it when I took you out. Often up to the moor, where we would park and I’d help you out of the car so that you could feel the air on your face and look at the view — a view you once loved to walk in. Every time I drove you back, the minute you saw the oak tree on the bend, you vocalised a sigh of helpless dread at being returned.

What would you both think of this memoir, I wonder. Dad, would you approve? I hope so. But I’m not sure. Interestingly, I think it would be you, Mum, who would be the most forceful in encouraging it. I think you would say, ‘you must write whatever you want, darling. It won’t work unless you do.’

I can hear the coarse clatter of typewriter keys. I can see you chain-smoking at the desk you inherited from your Great Aunt Emmy, furiously typing long letters with the intensity of Hemingway (although he probably wasn’t a pro touch typist, like you).

You wrote wonderful letters. Publishable letters. Letters containing astute and often very funny observations of people and events.

Laila and I read out extracts from your letters at a full-on cream tea celebration of your life several months after you died. I read the one you wrote to me during the Iranian Revolution when demonstrators stormed the British Embassy and set fire to it. You were alone in the ambassador’s residence when you heard ‘screams and explosions’. Your instinct was more curious than frightened; you climbed up the clock tower to get a good view: ‘Going up the ladder, I dislodged a mass of pigeons – parrots? – birds of some sort anyway – who were flying all around my face.’

We may not have given you a funeral, but we did you proud, mum. I think you would have enjoyed it … maybe.

You often said, or rather, declaimed: ‘I could have been a great novelist, but I’m too lazy.’ I agree on both counts. But I’ve come to hate the word lazy.

What other adjectives describe you? Brave? Yes. Adventurous? Yes. Reckless? Definitely. For you the edge of a cliff or a ‘No Trespass’ sign was an invitation; this impulse could either be a source of misery or fun for us. But organising a cocktail party for visiting MPs or arranging a seating plan for a dinner party was a jittery ordeal for you. The responsibilities of your role of diplomat’s wife filled you with neurotic dread. Neurotic. A word you might have used. A sharp word with a hint of criticism. I don’t think the word anxious was in vogue then. But it’s so clear to me now that you suffered from anxiety … and maybe a little bit of a disorder, Mum. What do you think?

I think being you was difficult — not just for us, but for you. Not all the time, Mum. But I’m just letting you know that I understand better now.

Anyway. I think both of you would be happier if I moved on to tennis. The sound of a tennis ball being hit back and forth. So many memories are contained in that sound. Many happy. Some not. I remember the sharp prick of ants biting my bare thighs on the hot grass beside the tennis courts in The British Club in Khartoum. The interminable boredom of having to sit and watch you both play — I longed not to hear the words, ‘Let’s play another set.’

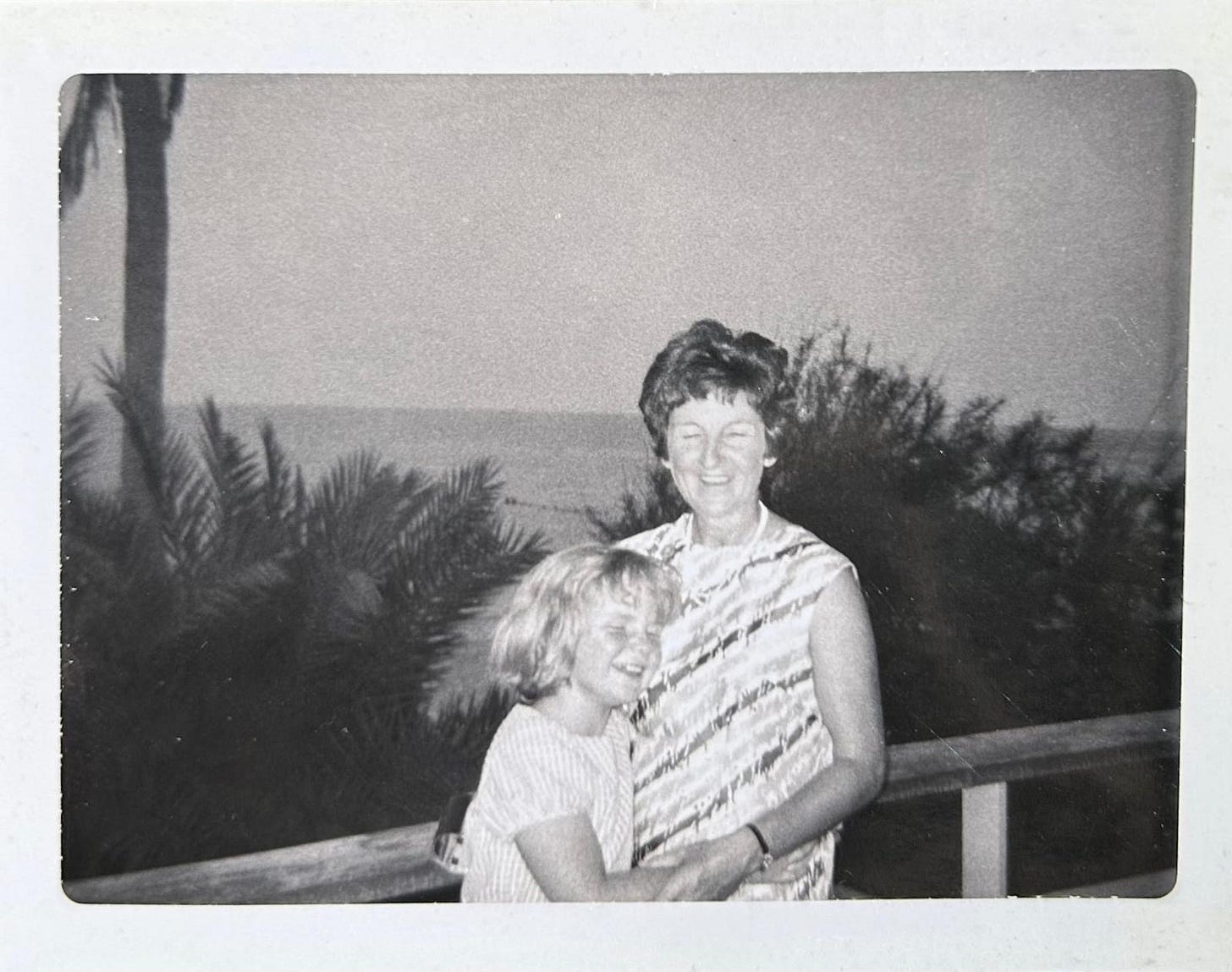

There’s something about tennis that symbolised your prioritising each other over us. It’s not me who is saying that. It’s you, mum. I remember you honestly saying that you felt guilty sometimes because you never wanted children, you just wanted to enjoy life with dad, but oh how happy you were that we came along! But tennis is also a precious memory of being very much included by you both. I remember the competitive fun and furious disputes of family tennis on several courts over several years to follow. Mum, if you were alive, you’d be cross with me for no longer playing tennis (apart from in an old static way with your sweet great-granddaughter, whom you’ll never know). You played until you were 74. Is that right, Mum? Until Dad died? I can see you now. On the court surrounded by lime trees in Devon. Cigarette in one hand, racquet in the other. And I can see you, Dad, diligently raking those infuriatingly sticky lime flowers off the court.

Tennis wasn’t the only thing you did together. You did everything together. You didn’t really have separate friends. Dad, you always said you refused invitations to men-only dinners because it was ridiculous that Mum couldn’t go, and you never became a member of one of those gentlemen’s clubs on Pall Mall, full of your tribe – end of empire ex-public schoolboys. Although, of course, in many ways you were that too … and something sometimes stirs inside me, a deep ancestral déjà vu (like when I watch The Jewel in the Crown — a programme you both loved because you could breathe its every sign and signifier).

If there’s an emerging theme in this memoir that I hadn’t reckoned on it’s the consistency of having felt loved by you both — from start to finish. Odd that isn’t it? Considering I also felt so abandoned. Or maybe feeling loved and abandoned at the same time isn’t incompatible.

So for the record, I love you both very much.

Emma

P.S. I think you’d be pleased to know that both your names are carved on to a slate headstone in Peter Tavy Churchyard. Yes! There. That beautiful place on the edge of Dartmoor so known and loved by both of you and all our family. On the back of the headstone is one of your favourite quotes:

The moving finger writes

And having writ

Moves on

Incredibly moving, Emma. She sounds amazing, but not a comfortable person to have as a mother. I wonder how many of our mothers of that generation had that feeling of being unfulfilled in themselves, and what effect that had on their relationships with us, their daughters? And her letters from the Iranian embassy are magnificent and deserve a wider audience.

It's very hard for me to write 'a comment' on the letters to Mum and Dad because they were my Mum and Dad too. However hard I try, I can't separate out your experience from mine even though I know our experiences were different. My responses are too big and inchoate for a comment box. But yes, one thing I know for sure is that we were fiercely loved and we loved them back. I also know for sure that you were a good daughter to Mum in those sad difficult years at the end (when yes, duty had to step in and give love some support). She was so lucky to have you always, but especially then. And I am brimful of gratitude for the burden you took on in her final years and carried with such strength.